"So we're doing this again?" I say as I read the first words.

Reading FW on the train could be an act of giving in, of not being able to control how people see you. I remember when studying for my PhD exams in Egyptology (this would be winter of 2015, the winter before Saoirse was born in May 2016), I would work late on campus two or three nights a week and travel home on the train (the L, this was Chicago) usually between the ungodly hours of 12 and 1 in the morning. Very few people riding then, but there I was reading books about Ancient Egypt on nearly empty trains, and waiting for someone to strike up a conversation. (Would the Bible have been any better?) I think it happened a few times and it was always interesting; once I remember someone talking to me about the pyramids (I was reading I. E. S. Edwards's book on the subject). I wish I would have recorded this then. Looking back now I realize that there really wasn't much of a difference between me and the odd people I would encounter, if we are talking about life decisions and ways in which we choose to sail our ship of life through the trackless seas of this world. Nothing happened today with FW on the train.

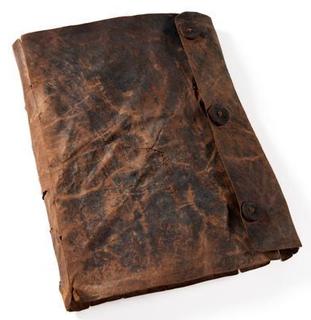

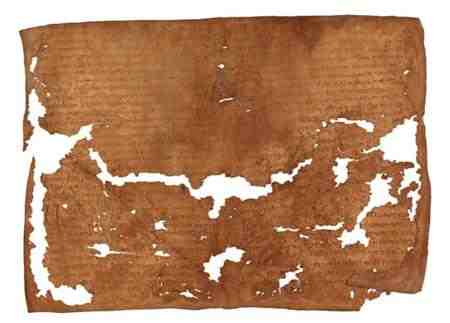

These are some of the most worn pages in my copy, and many of the notes I have scribbled in are so old I cannot read them; but many I can, and some are still helpful. At this stage I am thinking about buying a new copy and starting fresh, and annotating less on the level of word elucidation (annihilating the etyms) but giving guideposts for larger units.

My impression this time around after reading a pretty significant chunk of I.1 (I did about two days' worth, from last night to this evening), from the riverrun to right before the Prankqueen, and after the first few programmatic paragraphs, is the back-and-forth motion of the text, wavering from the wake of Finnegan and the still-visible monumental tomb in the landscape, to the landscape itself (not only with its ancient tombs but its museum, its trash piles), to the pages of the annal. While some of it, really most of it, seems to speak about what happened a long time ago (such as the Museyroom, the annal extract), I feel a sense of anticipation, like these figures are being introduced, like I am being told about the kind of thing they do, the understanding being this is what I am going to see or hear about. The deceased (at his wake, historic, or prehistoric), the deceased's wife (the searcher for traces, the archaeologist, the gatherer of clues, the tour guide, the keeper of the place; or are these latter ones a different figure, supposedly a Kate?), their children. HCE is gone (long gone or just), ALP is serving at his wake, and serving him, not just a communion but in preserving his memory, or even writing it. I keep reading until I "finally (though not yet endlike) meet with the acquaintance of Mister Typus, Mistress Tope and all the little typtopies. Fillstup" (p.20). Their existence, for me, will be on the page. HCE is the inverted letter sitting on the metal arm hovering in front of the page, the prototype, while ALP is place (not utopia but just "topia"), the blank page stretching before and after that will be filled with the letter marks. This strikes me as an almost literal way to describe how JJ populates his book.

I'm also told about this book itself: FW is telling me about itself. "So you need hardly spell me how every word will be bound over to carry three score and ten toptypsical readings throughout the book of Doublends Jined" (p.20). Seventy readings at least. I like how JJ says "readings" and not "meanings." So far I know this book described on these pages (the annal of Mammalujo, or even the odds and ends gathered by the hen) is of "Dublin's giant," but I will (in 64 days) know that it is the book of "double ends joined" that creates millions (generations, Heb. dor): "till Daleth...who oped it closeth therof the. Dor."

* * *

Silence: between the eras, but also silence itself can reach the page of the annalist, and not as an omission, for silence itself can be a fact. Silence after the thunder and the tumbling stonework, spreading downwards and preserved for ever in its falling motion. Frozen by moss and lichen, verdigris of copper hoarded in darkness, damp deep down. But in this annal there are no gaps between the years except for omission: scribal flight, scribicide? Some leaves are lost; may have been hidden due to damage to names no longer able to be said. They may turn up thousands of miles away, stuck carelessly between pages of a catalogue which no human is likely to ever open: a skipping stone cast into a dark and bottomless lake. Its cover however is intact and remains the same bluegreen. It may have been placed in the tomb of some unknown figure, passage tomb (or body transformed?) now visible only in grassy waves, as long as you are looking from far enough away, billowing earth overtaking collapse. If you can spot fifty, I can spot four more. The trained eye, or the unfocused eye deliberately made to be blurry, able to pick out from a swathe of greenscape from high vantage point of sea cliff those things that were deliberately made. Read the landscape, read the runes. The book survives, its connection remaining ever unclear; the runes are barely legible along the edge of the monolith.

* * *

|

"rory end to the regginbrow was to be seen ringsome on the aquaface"

(taken by me in Kill Devil Hills, NC, USA) |

Rot a peck of pa's malt had Jhem or Shen brewed by arclight and rory end to the regginbrow was to be seen ringsome on the aquaface. (3.12-14)

This has long been a line of interest for me. What I am writing now connects to a few days spent in the Regenstein library of the University of Chicago (in late June or early July 2011), before officially starting grad school but having just gotten access, looking at Joyceana in the stacks and trying to write my first article ever on the opening of FW; I should have been preparing for my upcoming program; the article is still unwritten, the notes are long lost.

This is the "red" sentence (German Rot, "red") at the end of a paragraph of sentences corresponding to the colors of the rainbow backwards (VIBGYOR). {Rot} is probably to be read "Not": all of these rainbow sentences are "and there was not yet" statements befitting a creation story (cf. Genesis 2:5-6: "...with no shrub of the field yet existing on the earth, with no greenery of the field yet sprouted, for Yahweh God had not made it rain on the earth, and as for a human being, there was not one to work the soil, but a wetness went up from the earth and watered the face of the soil."). The world of FW is not yet created, the type not yet met the pages; the only thing that is yet in the landscape of swerving shore and bending bay, standing at these castle ruins, is a rainbow. "The spirit of God hovered over the waters." The flood has already happened; inundation precedes creation.

Our cubehouse still rocks as earwitness to the thunder of his arafatas but we hear also through successive ages that shebby choruysh of unkalified muzzlenimiisilehims (5.13-17)

Does the sound still echo in the house (still rocks) or is the oral tradition not trustworthy, leaving us to face the speechless (still() signs that need to be deciphered on the stones (rocks), to be made into witnesses?

her birth is uncontrollable (11.33)

This is ALP, the faithful wife of Finnegan serving the guests at every wake, no matter how many happen. When HEC becomes part of the earth, only the humped outline of his tomb remaining, she is not buried next to him, but is an old woman, or a hen, picking or scratching around the surrounding fields and collecting signs of what has passed. Maybe even she is "writing" the "wrunes for ever" (19.36)? She is also Eve, punished to bear children in pain. She also continues to be born. How is the lifecycle of ALP in FW different from HCE? Here at the beginning, in her different forms, she seems an old woman. At the end of the book (IV), in the final section, isn't she a little girl again?

'Tis ontophone which ontophanes (13.16)

What is (

to ti ên einai) is revealed through sound.