Do we see ourselves in HCE?

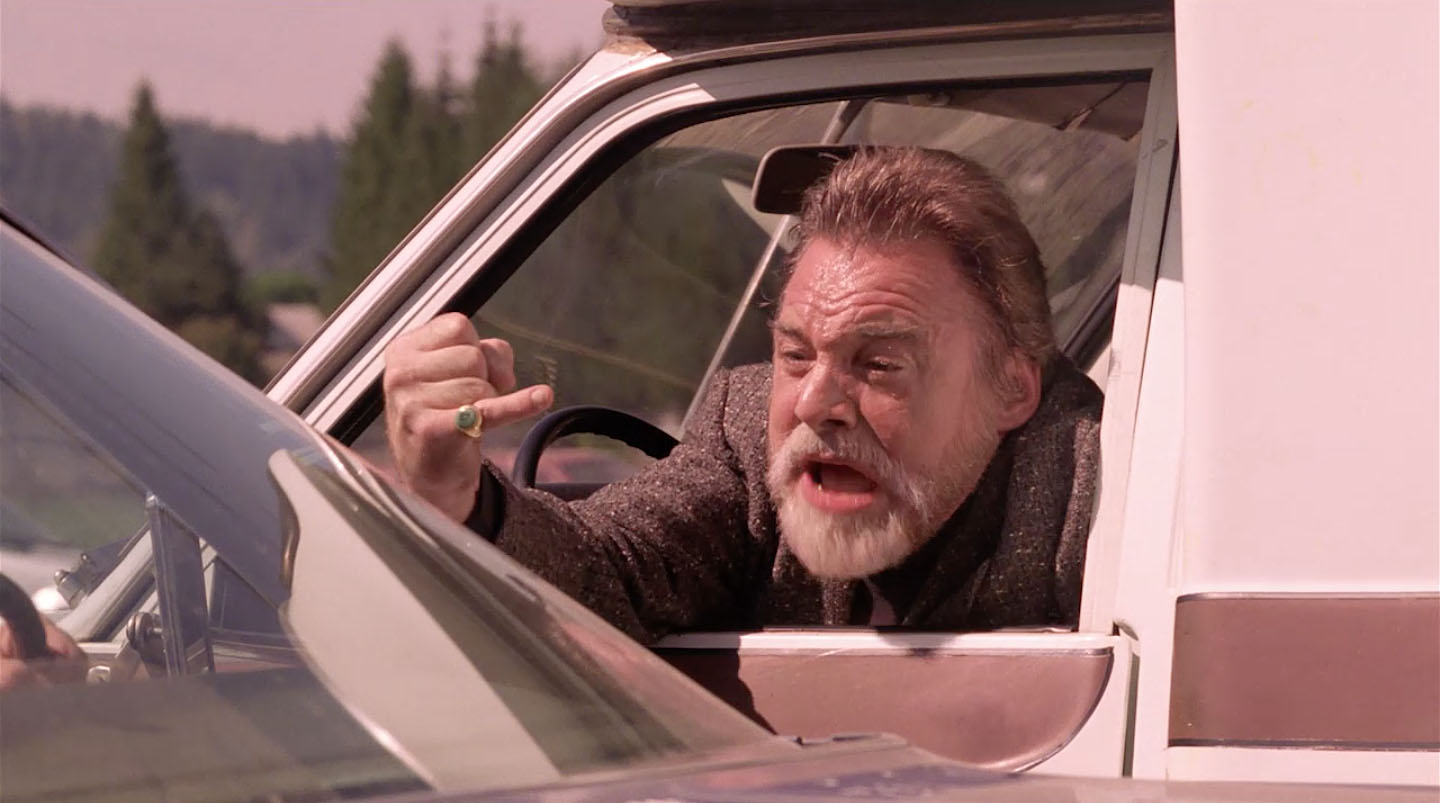

Your actions confused for something else, and even your attempt to correct the misapprehension is turned into a further affirmation, and even now a source of ridicule. H. is catching earwigs (garden pests), but thought by the king stopping on the highway, when seeing him come out from his yard, to be a lobster trapper (or perhaps a fisherman, since he is called a "pikebailer" by the king later). The king's question ("What kind of bait do you use?") is answered by Haromphreyld in the negative, and his explanation ("I was just catching earwigs") actually could be taken to be a direct answer (although I'm not sure if earwigs would work?). The king seems to continue to think of him as a fisherman of some sort, and ridicules Haromphreyld, who is supposed to be a "turnpiker" for the "bailiwick" (it is not clear if this is what H. actually is), for catching earwigs for these purposes.

Is the nickname endearing or hurtful? As "Here Comes Everybody," H. is a man of the people and "magnificently well worthy of any and all such universalisation," but is also too big to be contained in the space he inhabits (he seems to be both a giant and a man). Comically, when he sits in the theater he takes up so much space there is standing room only, "having the entirety of his house about him" (is this the first "she sits around the house" joke?).

You overshare. When someone asks you what time it is (the cad with the pipe), and, stammering, you assert your innocence against false accusations. You happen to be standing in the same place where the improprieties in said accusations are said to have taken place. This description of H. C. Earwicker's overreaction reminds me of the style of the Ithaca episode of Ulysses: "realising on fundamental liberal principles the supreme importance, nexally and noxally, of physical life...and unwishful as he felt of being hurled into eternity right then..."

* * *

Slow, or close reading and quick, paragraph-by-paragraph reading are the two modes I work in, but their harmonious interaction is hampered by a refusal to be able to understand detail fully until the whole can come into view for me. I am good at making leaps in that direction (the latter) and sometimes even can gain good insights on a text as a whole based on instinct and cursory small-scale looks. But I can also be wildly wrong. I’m also stubborn and have a hard time moving past first impressions once the minuter data begin accumulating.

Working on texts in foreign languages, which is most of what I do professionally, makes this harder. I can’t read quickly as well as in English, and when it comes to the details, the word-by-word, it is easy to do endless dictionary work. Combine that with my natural paranoia that an answer has already been found, a correct reading out there in print (or, even worse, part of the Requisite Knowledge I’m to have deeply internalized and to have ready to fire like a shot out of a pistol), the reading and interpretive process can be a slow, tortuous, hesitating, unfulfilling process, the latter occurring when I realize I’ve been too long on the trail and have lost the momentum of the hunt.

Reading FW at this pace for “FW65” feels like a training regimen for working through this ingrained dialectical hesitation of my reading and writing method. More so than any ancient text, FW rewards minutest attention and slowest reading. But it is also, as JJ said, music, and music does not have to mean anything, it can just be (“you are the music while the music lasts”). It also has to be heard on its own pace, and that does not always (probably never) mean 10 beats per minute.

I sense a reason for a feeling I have always had, that reading really difficult texts is to be preferred because you already know that, at each encounter, you will only arrive at part of the truth. That an interplay between knowing and unknowing is built into the very stuff, making the moments of illumination precious, as well as, by design, accompanied by a humble reminder that there is more to come.

No comments:

Post a Comment